The major Indices tracked sideways this week, risk indicators were neutral, with markets absorbing mixed to good news on earnings, indications that the US economy is generally slowing, and inflation moderating. Traders are prepping for a quarter point rate rise at the next FOMC meeting on May 5-6.

In this, our first Friday Briefing, we provide some context on market valuations and highlight risk at this late, late stage in the Bull market. Stocks have been rising for over 14 years, if we date the last major Bear market low in March 2009. Opinions vary, but typical bull markets are between 7 and 9 years. It’s worth thinking about why this rally was so prolonged, and what might bring it to an end.

First, cast your thoughts back to the start of this Bull market. The Mortgage/Credit crisis was two years old, house prices were tanking (bottoming in the early fall of 2009), the economic recession was bottoming out, largely thanks the Fed was supporting banks and the economy with an accommodative balance sheet and zero rate interest rates. Unsurprisingly, risk assets went on the longest tear of a generation.

Now, contrast this with where we are today. Money center banks are generally healthy, the housing market is healthy (after a long boom), and we are speculating about high the Fed must ratchet up rates to curb inflation, and the impact on a buoyant economy. Where does this leave risk assets? Arguably close to the end of the party than the beginning.

Arlan Suderman, StoneX’s Commodity Economist has made the point that the Fed is very focused on not repeating historic mistakes to stem inflation, doing too little too late. The Fed will raise rates until inflation is curbed.

Let’s start with the outlook for long rates. Vincent Deluard, StoneX’s Global Strategist, was arguing for an upturn in 10 year bond yields back in February (‘Introducing the StoneX Treasury Market Liquidity Scorecard’) based on supply and demand fundamentals. While not picking a forecast, it’s interesting to note that long rates appear to be reversing their four-plus decades decline.

We will discuss what equilibrium long rates ought to be in future comments, but for now let’s assume that 6% is possible in the next 12-18 months (a rate last seen twenty-years ago).

Source: StoneX, Robert J. Shiller, Yale University.

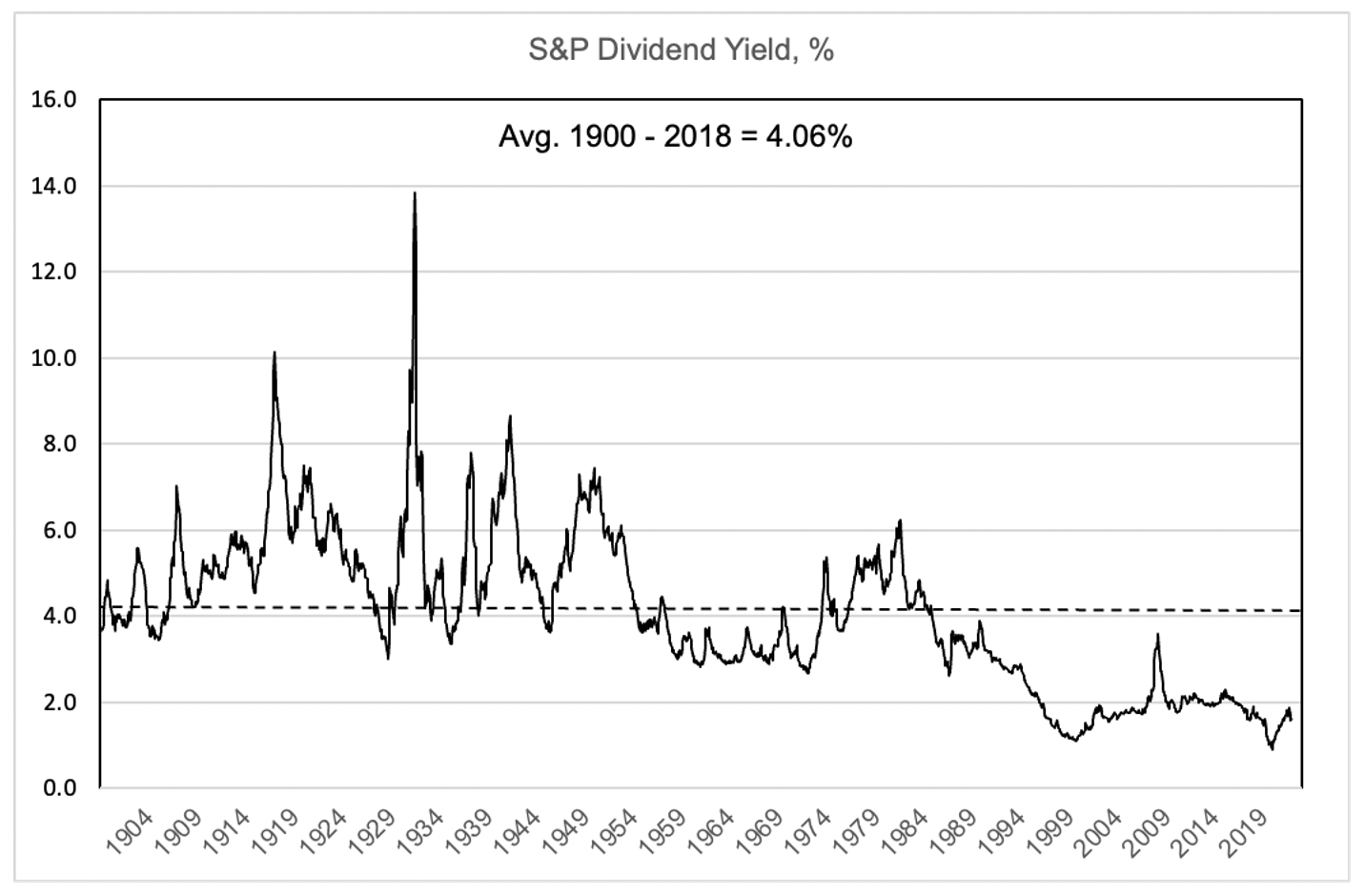

Now turning to equity market valuations, lets put today’s equity markets in the context of long-run dividend yields. Some might say that more than a century of data is too much, but we can focus on the post-Second World War period as being representative of the modern era of equity investing.

In this period, reported dividend yields on the S&P 500 fell from around 4%, the long-run average, to around 2% (and today, 1.7%). Arguably, this is a high valuation for equities, until one contrasts it with lower long rates.

Source: StoneX, Shiller (ibid), S&P.

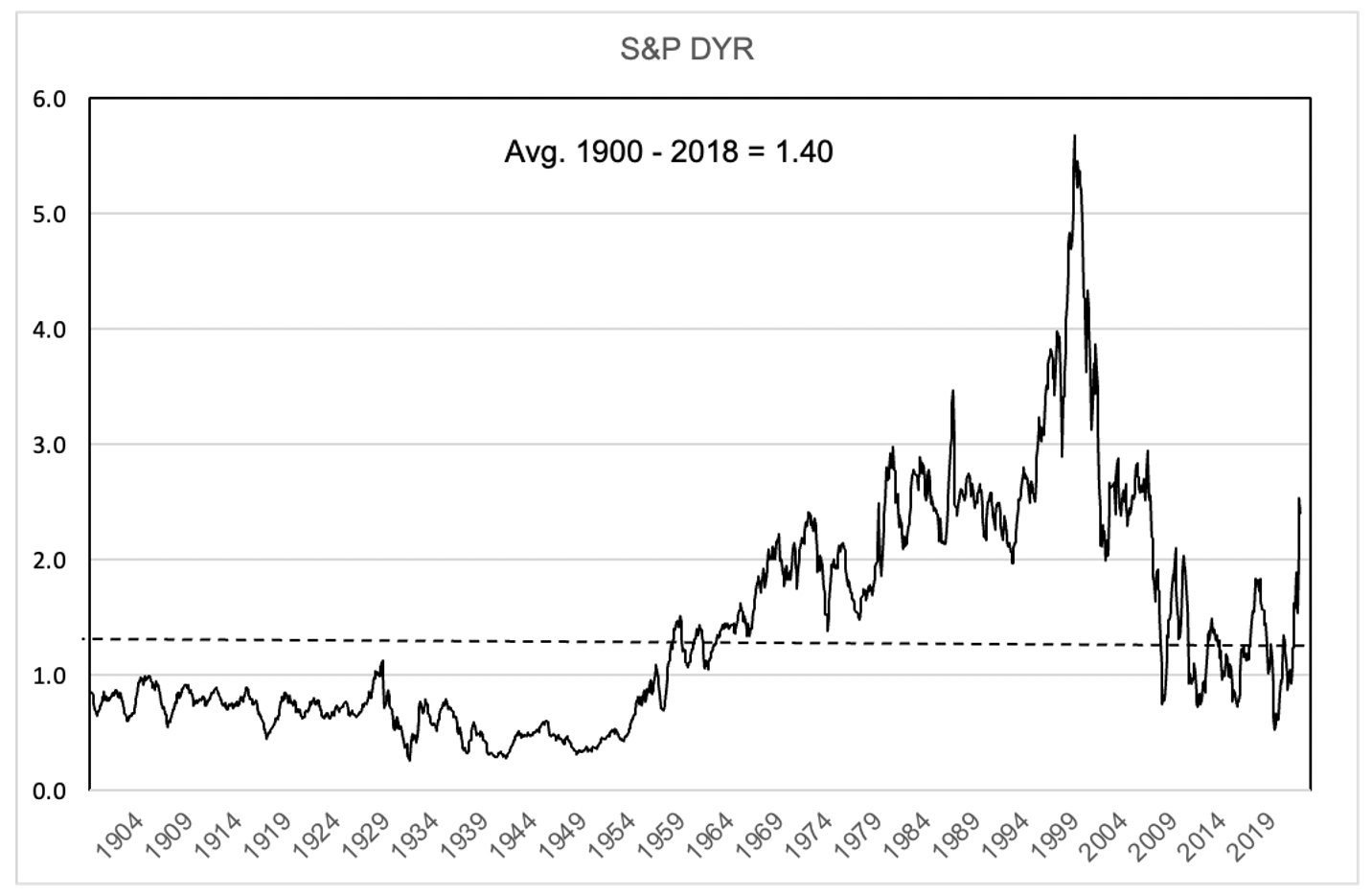

Dividend yields are typically compensated with dividend growth and this together generates total return which should justify these yields being lower than bond yields. The key question is: how much lower? A final valuation tool in our arsenal is the Dividend Yield to Bond Yield Ratio, or DYR.

When bonds yield a lot more than equities (as long rates are high, or equity yields are low) we can argue that the equity market is looking over-valued. In other words, investors are overestimating the pace of future dividend growth to raise equity yields and close the gap with bond yields.

The DYR has been a useful measure of future trouble for Indices, most notably at the peak of the Tech bubble in the late 1990s, when the DYR hit 5.6 – four times above average – and the equity market saw a sharp correction.

When equity investors realized that stocks couldn’t possibly growth fast enough to justify these valuations, and dividend growth was in any case sluggish, equity prices slid.

Source: StoneX, Shiller (ibid), S&P.

What do we conclude for markets today? Regardless of the current sanguine market, there are three risks. First, long rates could continue their reversal to more normal levels (assume 6%?). Second, the rating of equities could slip versus bonds (assume a 1.5 DYR?). This combination produces a target dividend yield of 4%, in line with long-run averages. If, and it’s a theoretical ‘if’ and not a forecast, the target level for the S&P 500 would 60% lower than today’s 4,130 –back to the 2,375 last seen in the spring of 2020.

By way of caution, all three factors would be need for this Bear market sell-off. Where could we be wrong? First, rising long rates might not happen – an economic recession could invalidate this argument, and rates could move lower. Second, the de-rating of equity markets is an infamously difficult call to make. Equities often traded rich for long periods. However, we would conclude that there is more risk in equity markets than many seem to acknowledge, and the current sanguine outlook is perhaps too rosy.

Analysis by Paul Walton, Financial Writer

Contact: [email protected]